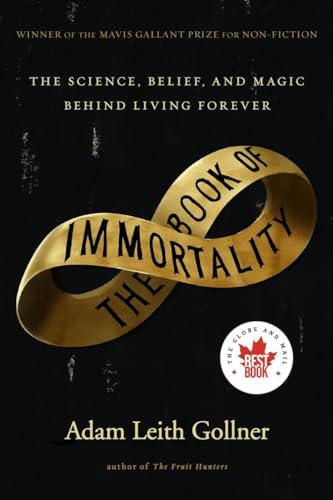

Items related to The Book of Immortality

"Gollner goes to the ends of the earth to talk to people who want to beat the clock--forever. So far, there's no proof of success, but their efforts prove entertaining, and, through Gollner's lens, touching as well." The Globe and Mail

The author of the widely acclaimed The Fruit Hunters weaves together religion, science and magic in this Mark Kurlansky-style exploration of the most universal of human obsessions, immortality.

With his singular curiosity, Gollner delves into a strange array of contemporary and historical characters and cults, religions and myths, and businesses all devoted to some form of immortality. His journey begins at a costume party thrown by a group of immortalists in California and ends on David Copperfield's archipelago in the Bahamas, where Copperfield claims to have found the fountain of youth. Along the way he visits St. Augustine, Florida and its purported fountain of youth; Harvard University, where he attends an anti-aging symposium; and Esalen, where he meets a whole host of quirky characters who embody our fascination with escaping death.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

It is apparent that there is no death.

But what does that signify?

—Edna St. Vincent Millay, “Spring”

Because they believed in nothing, they were ready to believe anything.

—Lucian Boia, Forever Young

IMMORTALITY DOESN’T ACTUALLY EXIST. It’s not something tangible we can point to, see, or demonstrate. It resides in thought but not in reality. Immortality is an abstract concept that helps us make sense of death. The idea emerged from our fear of dying, from the sense that life must go on in some way.

Immortality means nonmortality, undeath, never-ending existence in this world or some other. It is the permanent absence of death. It entails evading or outliving the end. But that can’t be done, or at least we can’t prove that it can be done. No examples of anything immortal have ever been found by science. There are just visions, tales, hopes, fears, and maybe some inferential cognizers.

In most definitions, immortality occurs after death. The unending perseverance of a mind or a soul following the decay of the physical body is spiritual immortality. The basic premise of this cosmology is simple: we die but our soul (or some other part) doesn’t. Just as our flesh must necessarily decay, our spirit or intellect or entelechy returns to the primordial source. An energy or force within us outlives its mortal container, ending up in the afterlife or hurled back into rebirth.

Spiritual immortality is a narrative of numberless incarnations, from eternal sanctification to damnation to reincarnation. The very word immortality conceals infinite possibilities. It’s a one-word poem. It can mean whatever we want it to mean, whatever we believe it to mean. In recent years, the idea of the indefinite persistence of an undying material body has captivated us. But physical immortality is also a mythology. It, too, helps followers cope with an uncertain world, just as a Christian uses the idea of redemption.

We tend to imagine that these are secular times. The facts suggest otherwise. Belief in posthumous immortality is very much alive today. Data collected by the General Social Surveys show that 80 percent of Americans believe in life after death. The figures are around 70 percent in Canada, 65 percent in Australia, 60 percent in the UK, and above 50 percent throughout much of Europe. According to the World Values Survey, close to 100 percent of those surveyed in parts of the Middle East believe in the afterlife. Not exactly a faithless world.

For those of us who don’t believe in immortality, we can either dismiss it or contemplate it. Either way, it’s not something we can resolve. Immortality is a matter of belief, not fact. Like death, immortality is something we dance with. But there’s no denying the existence of death. We can believe we won’t die, but dying is ineluctable, devastating, real.

Every single day around two hundred thousand people die worldwide. There are two deaths every second. Six people just died. Make that eight. Ten. It can happen to anybody at any time, and yet exposure to death profoundly bothers our mind precisely because we can’t understand it. Death is what’s called a “meaning threat.” When confronted with the incomprehensible—such as losing a loved one—our mind scrambles to find another pattern that alleviates the confusion. For some, it’s enough to say, “They’re gone.” Others have such an urgent need to escape feelings of meaninglessness that they create alternate, more coherent plausibilities, such as myths about immortality.

Grief forces us to have an opinion about the end. Imagining that everlasting life exists is a common reaction. We tell ourselves the loved one is somewhere else now, somewhere better. To make sense of insensateness, we wrap ourselves in beliefs. We’re all apprentice magicians trying to master the trick that transforms loss into understanding.

Thoughts of eternal life shuttle between the terminals of knowledge and belief. There are things we can know and things we can’t know. The knowables are gathered into knowledge. We deal with everything else through belief. Science is our means of exploring all that can be known; belief is how we approach that which cannot be known. Beliefs allow the brain to assert truths when lacking material evidence. Death tells us nothing knowable, only that we are currently alive and that our bodies won’t last forever.

As a result, psychologists claim we’re all frightened of dying, but it isn’t simply anticipatory worry; it’s the not knowing that bothers us, the lack of control. What we want is something that doesn’t exist: resolution.

Because patternlessness cannot be borne, the brain represses thoughts of its eventual extinction. It’s impossible to understand what it would be like to have no more thoughts. We have a central incapacity, a bug built into the operating system: our consciousness cannot imagine a lack of consciousness. Trying to imagine our own death is like trying to think thought. We cannot do it. “Try to fill your consciousness with the representation of no-consciousness, and you will see the impossibility of it,” wrote Unamuno. “The effort to comprehend it causes the most tormenting dizziness. We cannot conceive ourselves as not existing.”

Nonexistence is nonconceivable. The brain conceptualizes things as being somehow similar to other conceivable things, so we compare death to life, minus the body—which is why we imagine that our consciousness (whatever that is) will outlive us. All our fantasies of stymieing the inevitable stem from an inability to grasp the fact of finality.

Consider what would happen if certain species did not die. They would simply keep on breeding and accumulating. In the time it takes to read this sentence, several hundred million ants will have been born across the planet. It would take a single tiny bacterium mere hours to generate a mass equivalent to that of a human child—and there are countless billions of bacteria within a hundred-foot radius of everyone. Imagine if they could live forever? “In less than two days, the entire surface of the earth would be covered in great smelly dunes of prettily colored bacteria,” explains zoologist Lyall Watson. “Left similarly unhindered, a protozoan could achieve the same end in forty days; a house fly would need four years; a rat eight years; a clover plant eleven years; and it would take almost a century for us to be overwhelmed by elephants.” We can thank death for the fact that our atmosphere isn’t clogged with hedgehogs all the way to the ozone layer. Like everything else in nature, we’re all terminal cases.

The oldest person who ever lived whose true age could officially be verified died at 122 in 1997. (She only gave up smoking at 119.) From the dawn of the Homo genus up to the 1800s, the majority could expect to live for approximately twenty-five to forty years. Largely due to basic realizations about hygiene, life expectancy has increased significantly over the past century and a half. Some demographers argue that life spans have attained their utmost and are starting to decrease slightly. Others disagree, suggesting that 125 is a reasonable target for baby boomers. Most scientists maintain that human life has a maximum expiry date, but immortalists speak of Plastic Omega (omega being the end of life, and plastic being malleable). As of 2013, all parties can anticipate living somewhere between seventy to ninety years unless an accident, disease, or disaster strikes—or immortality becomes reality.

Intriguing, genuine discoveries are being made in the field of gerontological studies. Scientists have dramatically increased the life spans of simple organisms such as yeast, roundworms, fruit flies, even mice. So far, those breakthroughs haven’t yielded human applications. But even if we learned to cure every major disease, to resolve every cause listed on death certificates, some biologists argue, we’d still only add ten or fifteen years to human life expectancy. Research being made on a genetic level could eventually prove beneficial to our health span. Even so, death will become us.

There’s an important distinction between medicine and miracle work: miracles prevent death; medicine counteracts illness. The main aim of mainstream medicine is prolonging health, and contemporary doctors know more about keeping people alive than ever before. That doesn’t mean we can make people stop dying. The average Westerner only gets eighty years, not eighty trillion. And there’s a price to pay for extended life: the degenerative diseases of senescence. Our bodies aren’t supposed to live forever, which is why they have built-in obsolescence mechanisms.

Longevity is starkly different from immortality, yet somehow the two have fused in public consciousness. Most of us will live longer than our ancestors did, but all of us can still die at any moment. Spurred on by our gains in life expectancy, a pandemic of magical thinking about science’s unlimited capabilities has led to a wider discussion about the possibility of eternal life.

Prime-time TV specials with titles like “Can We Live Forever?” fuel the mass delusion. Every year more conferences pop up purporting to reveal the latest means of attaining eternity through technology. “Immortality Only 20 Years Away,” blare newspaper headlines. Philanthropic organizations (the Immortality Institute, the Methuselah Foundation, the Fuck Death Foundation) are joining together to eliminate death. “There are people living today who may extend their life spans indefinitely,” declare salesmen, triangulating faith, biology, and magic into a unified worldview.

This confusion has led to an alarming increase in the availability of untested antiaging remedies over the past two decades. Countless products are presently being sold as having life-extending qualities, even though there aren’t any demonstrable means of increasing human life. “No treatments have been proven to slow or reverse the aging process,” announced the National Institute on Aging in 2009, trying to staunch the hype. Contrasting the claims made by life-extension companies with the genuine science of aging, fifty-two scientists signed a “Position Statement” on longevity that clarified the situation explicitly: no currently marketed intervention—none—has yet been able to stop or even affect human aging. “The prospect of humans living forever is as unlikely today as it has always been,” they wrote, “and discussions of such an impossible scenario have no place in a scientific discourse.”

The dominant mythology of triumphalist scientism is the idea of progress. For the most part, we don’t question the idea that everything is constantly getting better and better and better. It’s just the way things are, we tell ourselves. We’re so close to perfection. And progress necessarily leads somewhere: to a world in which we’re all immortal.

A solid belief system is one we don’t realize is a belief system. Because science’s veritable achievements are so impressive, almost everybody today believes in the unidirectional march of progress. Technology is unceasingly propelling us forward, and science has become synonymous with progress, so it becomes easy to imagine that life everlasting is around the corner. We take it for granted that suffering can be eliminated, that poverty will ultimately be eradicated, that we should never be sick again, that science will soon make everybody never die. The illusion of continual betterment is a pervasive enough mythology that it can overlook the environmental crises, the scale of warfare, and the fact that over a billion people live on less than $1 per day.

Is progress even real? Microchips certainly get smaller and processing speeds faster, but not everything has progressed over the past centuries. Have our emotions changed since Shakespeare’s time? Since Sophocles’s time? Are we moving toward a time of universal happiness? Genocide is not an anachronism. Neither is inequality. Is progress a law of history, or is it a story we tell ourselves?

In 1869, the avant-garde writer Comte de Lautréamont published Les Chants de Maldoror, a book exploring “the spiritual crisis brought on by scientific progress.” In it, he characterized immortality as “the terrifying problem that humanity has not yet solved.” A century and a half later, we’re still nowhere close to solving it.

Although our congenital belief in progress means we’re more ready than ever before to believe in physical immortality, misinformed life-extension stories have been around for millennia. There’s nothing new about bearded hustlers such as Aubrey de Grey vowing to help us live forever and cryonicists who claim to have “cured death itself.” They’re all tapping into a longing that has always been with us.

Yellowing medical journals are filled with stories about how “the great alchemical dream, the ‘Elixir of Life,’ seems almost ready to be bottled.” Following World War II, the personal goal of attaining immortality moved from religious aspiration to “actual possibility.” In 1966, biophysicists at the California Institute of Technology wrote, “We know of no intrinsic limits to the life span.” In the 1970s, a group of molecular biologists and gerontologists mobilized as “the Immortalist Underground.” In 2010, a special issue of Time magazine about longevity announced that “elixirs of youth sound fanciful, but the first crude anti-aging drugs may not be so far away.”

We’re drowning in misinformation. How-to books such as Why Die? A Beginner’s Guide to Living Forever and Young Again! How to Reverse the Aging Process and Physical Immortality: The Science of Everlasting Life each outline various ways to defeat reality by harnessing miracles of technology. Finding such miracles is abundantly easy, especially online. Searching “immortality device wanted” leads to a site called www.achieveimmortality.com that claims to own US patent number 5,989,178 for “the most imporatnt [sic] invention in human history,” a gear-based magnetic pinkie ring that “ALLOWS HUMANS TO STAY PHYSICALLY YOUNG FOREVER.”

Entire subcultures of enthusiasts are dedicated to deathlessness. There are bloggers with “a passion to create an environment where all sickness, aging and death are eliminated.” There are amateur philosophers who argue that everyone is bodily immortal until proven otherwise. Facebook Transhumanists list their religious views as “the abolition of suffering.” They end posts with the movement’s abbreviation: H+, as in “human plus.” Superlongevist manifestos confidently assert that we can all live for hundreds of years, that the “eventuality” of a “modern Fountain of Youth” is nigh.

It is utterly ordinary to not want to die. But, as Dame Edith Sitwell once wrote, ordinariness carried to a high degree of perfection is precisely the definition of eccentricity. In her view, eccentricity entails “some rigid, and even splendid, attitude of Death, some exaggeration of the attitudes common to Life.” As she concluded, there’s something askew about people who don’t understand they will die—or that they are actually dead, in the case of cryonicists buried upside down in frozen thermoses, five per container, wrapped in sleeping bags, awaiting reanimation.

Eccentrics really, really don’t want to die. Caloric restrictors, sun gazers, nightwalkers, potion peddlers, cybernetic Nostradamus-types, and outright charlatans: the immortality community boasts a plethora of unorthodox individuals. Most noneccentrics consider physical immor...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAnchor Canada

- Publication date2014

- ISBN 10 0385667310

- ISBN 13 9780385667319

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages416

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Book of Immortality

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.75. Seller Inventory # G0385667310I3N00

The Book of Immortality

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.75. Seller Inventory # G0385667310I3N00