Items related to Expecting Better: Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom...

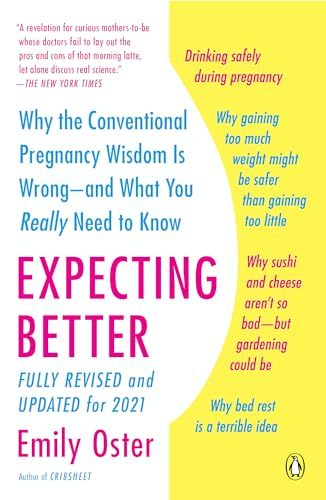

Expecting Better: Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom Is Wrong--and What You Really Need to Know (The ParentData Series) - Softcover

What to Expect When You're Expecting meets Freakonomics: an award-winning economist disproves standard recommendations about pregnancy to empower women while they're expecting. From the author of Cribsheet, a data-driven decision making guide to the early years of parenting

Pregnancy—unquestionably one of the most pro≠found, meaningful experiences of adulthood—can reduce otherwise intelligent women to, well, babies. Pregnant women are told to avoid cold cuts, sushi, alcohol, and coffee without ever being told why these are forbidden. Rules for prenatal testing are similarly unexplained. Moms-to-be desperately want a resource that empowers them to make their own right choices.

When award-winning economist Emily Oster was a mom-to-be herself, she evaluated the data behind the accepted rules of pregnancy, and discovered that most are often misguided and some are just flat-out wrong. Debunking myths and explaining everything from the real effects of caffeine to the surprising dangers of gardening, Expecting Better is the book for every pregnant woman who wants to enjoy a healthy and relaxed pregnancy—and the occasional glass of wine.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Introduction

In the fall of 2009 my husband, Jesse, and I decided to have a baby. We were both economics professors at the University of Chicago. We’d been together since my junior year of college, and married almost five years. Jesse was close to getting tenure, and my work was going pretty well. My thirtieth birthday was around the corner.

We’d always talked about having a family, and the discussion got steadily more serious. One morning in October we took a long run together and, finally, decided we were ready. Or, at the very least, we probably were not going to get any more ready. It took a bit of time, but about eighteen months later our daughter, Penelope, arrived.

I’d always worried that being pregnant would affect my work—people tell all kinds of stories about “pregnancy brain,” and missing weeks (or months!) of work for morning sickness. As it happens, I was lucky and it didn’t seem to make much difference (actually having the baby was another story).

But what I didn’t expect at all is how much I would put the tools of my job as an economist to use during my pregnancy. This may seem odd. Despite the occasional use of “Dr.” in front of my name, I am not, in fact, a real doctor, let alone an obstetrician. If you have a traditional view of economics, you’re probably thinking of Ben Bernanke making Fed policy, or the guys creating financial derivatives at Goldman Sachs. You would not go to Alan Greenspan for pregnancy advice.

But here is the thing: the tools of economics turn out to be enormously useful in evaluating the quality of information in any situation. Economists’ core decision-making principles are applicable everywhere. Everywhere. And that includes the womb.

When I got pregnant, I pretty quickly learned that there is a lot of information out there about pregnancy, and a lot of recommendations. But neither the information nor the recommendations were all good. The information was of varying quality, and the recommendations were often contradictory and occasionally infuriating. In the end, in an effort to get to the good information—to really figure out the truth—and to make the right decisions, I tackled the problem as I would any other, with economics.

At the University of Chicago I teach introductory microeconomics to first-year MBA students. My students would probably tell you the point of the class is to torture them with calculus. In fact, I have a slightly more lofty goal. I want to teach them decision making. Ultimately, this is what microeconomics is: decision science—a way to structure your thinking so you make good choices.

I try to teach them that making good decisions—in business, and in life—requires two things. First, they need all the information about the decision—they need the right data. Second, they need to think about the right way to weigh the pluses and minuses of the decision (in class we call this costs and benefits) for them personally. The key is that even with the same data, this second part—this weighing of the pluses and minuses—may result in different decisions for different people. Individuals may value the same thing differently.

For my students, the applications they care about most are business-related. They want to answer questions like, should I buy this company or not? I tell them to start with the numbers: How much money does this company make? How much do you expect it to make in the future? This is the data, the information part of the decision.

Once they know that, they can weigh the pluses and minuses. Here is where they sometimes get tripped up. The plus of buying is, of course, the profits that they’ll make. The minus is that they have to give up the option to buy something else. Maybe a better company. In the end, the decision rests on evaluating these pluses and minuses for them personally. They have to figure out what else they could do with the money. Making this decision correctly requires thinking hard about the alternative, and that’s not going to be the same for everyone.

Of course, most of us don’t spend a lot of time purchasing companies. (To be fair, I’m not sure this is always what my students use my class for, either—I recently got an e-mail from a student saying that what he learned from my class was that he should stop drinking his beer if he wasn’t enjoying it. This actually is a good application of the principle of sunk costs, if not the primary focus of class.) But the concept of good decision making goes far beyond business.

In fact, once you internalize economic decision making, it comes up everywhere.

When Jesse and I decided we should have a baby, I convinced him that we had to move out of our third-floor walk-up. Too many steps with a stroller, I declared. He agreed, as long as I was willing to do the house shopping.

I got around to it sometime in February, in Chicago, and I trekked in the snow to fifteen or sixteen seemingly identical houses. When I finally found one that I liked (slightly) more than the others, the fun started. We had to make a decision about how much to offer for it.

As I teach my students, we started with the data: we tried to figure out how much this particular house was worth in the market. This wasn’t too difficult. The house had last sold in 2007, and we found the price listed online. All we had to do was figure out how much prices had changed in the last two years. We were right in the middle of a housing crisis—hard to miss, especially for an economist—so we knew prices had gone down. But by how much?

If we wanted to know about price changes in Chicago overall we could have used something called the Case-Shiller index, a common measure of housing prices. But this was for the whole city—not just for our neighborhood. Could we do better? I found an online housing resource (Zillow.com) that provided simple graphs showing the changes in housing prices by neighborhood in Chicago. All we had to do was take the old price, figure out the expected change, and come up with our new price.

This was the data side of the decision. But we weren’t done. To make the right decision we still needed the pluses and minuses part. We needed to think about how much we liked this house relative to other houses. What we had figured out was the market price for the house—what we thought other people would want to pay, on average. But if we thought this house was really special, really perfect, and ideal for us in particular, we would probably want to bid more than we thought it was worth in the market—we’d be willing to pay something extra because our feelings about this house were so strong.

There wasn’t any data to tell us about this second part of the decision; we just had to think about it. In the end, we thought that, for us, this house seemed pretty similar to all the other ones. We bid the price we thought was correct for the house, and we didn’t get it. (Maybe it was the pricing memo we sent with our bid? Hard to say.) In the end, we bought another house we liked just as much.

But this was just our personal situation. A few months later one of our friends fell in love with one particular house. He thought this house was a one-of-a-kind option, perfect for him and his family. When it came down to it, he paid a bit more than the data might have suggested. It’s easy to see why that’s also the right decision, once you use the right decision process—the economist’s decision process.

Ultimately, as I tell my students, this isn’t just one way to make decisions. It is the correct way.

So, naturally, when I did get pregnant I thought this was how pregnancy decision making would work, too. Take something like amniocentesis. I thought my doctor would start by outlining a framework for making this decision—pluses and minuses. She’d tell me the plus of this test is you can get a lot of information about the baby; the minus is that there is a risk of miscarriage. She’d give me the data I needed. She’d tell me how much extra information I’d get, and she’d tell me the exact risk of miscarriage. She’d then sit back, Jesse and I would discuss it, and we’d come to a decision that worked for us.

This is not what it was like at all.

In reality, pregnancy medical care seemed to be one long list of rules. In fact, being pregnant was a lot like being a child again. There was always someone telling you what to do. It started right away. “You can have only two cups of coffee a day.” I wondered why—what were the minuses (I knew the pluses—I love coffee!)? What did the numbers say about how risky this was? This wasn’t discussed anywhere.

And then we got to prenatal testing. “The guidelines say you should have an amniocentesis only if you are over thirty-five.” Why is that? Well, those are the rules. Surely that differs for different people? Nope, apparently not (at least according to my doctor).

Pregnancy seemed to be treated as a one-size-fits-all affair. The way I was used to making decisions—thinking about my personal preferences, combined with the data—was barely used at all. This was frustrating enough. Making it worse, the recommendations I read in books or heard from friends often contradicted what I heard from my doctor.

Pregnancy seemed to be a world of arbitrary rules. It was as if when we were shopping for houses, our realtor announced that people without kids do not like backyards, and therefore she would not be showing us any houses with backyards. Worse, it was as if when we told her that we actually do like backyards she said, “No, you don’t, this is the rule.” You’d fire your real estate agent on the spot if she did this. Yet this is how pregnancy often seemed to work.

This wasn’t universal, of course; there were occasional decisions to which I was supposed to contribute. But even these seemed cursory. When it came time to think about the epidural, I decided not to have one. This wasn’t an especially common choice, and the doctor told me something like, “Okay, well, you’ll probably get one anyway.” I had the appearance of decision-making authority, but apparently not the reality.

I don’t think this is limited to pregnancy—other interactions with the medical system often seem to be the same way. The recognition that patient preferences might differ, which might play an important role in deciding on treatment, is at least sometimes ignored. At some point I found myself reading Jerome Groopman and Pamela Hartzband’s book, Your Medical Mind: How to Decide What Is Right for You, and nodding along with many of their stories about people in other settings—prostate cancer, for example—who should have had a more active role in deciding which particular treatment was right for them.

But, like most healthy young women, pregnancy was my first sustained interaction with the medical system. It was getting pretty frustrating. Adding to the stress of the rules was the fear of what might go wrong if I did not follow them. Of course, I had no way of knowing how nervous I should be.

I wanted a doctor who was trained in decision making. In fact, this isn’t really done much in medical schools. Appropriately, medical school tends to focus much more on the mechanics of being a doctor. You’ll be glad for that, as I was, when someone actually has to get the baby out of you. But it doesn’t leave much time for decision theory.

It became clear quickly that I’d have to come up with my own framework—to structure the decisions on my own. That didn’t seem so hard, at least in principle. But when it came to actually doing it, I simply couldn’t find an easy way to get the numbers—the data—to make these decisions.

I thought my questions were fairly simple. Consider alcohol. I figured out the way to think about the decision—there might be some decrease in child IQ from drinking in pregnancy (the minus), but I’d enjoy a glass of wine occasionally (the plus). The truth was that the plus here is small, and if there was any demonstrated impact of occasional drinking on IQ, I’d abstain. But I did need the number: would having an occasional glass of wine impact my child’s IQ at all? If not, there was no reason not to have one.

Or in prenatal testing. The minus seemed to be the risk of miscarriage. The plus was information about the health of my baby. But what was the actual miscarriage risk? And how much information did these tests really provide relative to other, less risky, options?

The numbers were not forthcoming. I asked my doctor about drinking. She said that one or two drinks a week was “probably fine.” “Probably fine” is not a number. The books were the same way. They didn’t always say the same thing, or agree with my doctor, but they tended to provide vague reassurances (“prenatal testing is very safe”) or blanket bans (“no amount of alcohol has been proven safe”). Again, not numbers.

I tried going a little closer to the source, reading the official recommendation from the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Interestingly, these recommendations were often different from what my doctor said—they seemed to be evolving faster with the current medical literature than actual practice was. But they still didn’t provide numbers.

To get to the data, I had to get into the papers that the recommendations were based on. In some cases, this wasn’t too hard. When it came time to think about whether or not to get an epidural, I was able to use data from randomized trials—the gold standard evidence in science—to figure out the risks and benefits.

In other cases, it was a lot more complicated. And several times—with alcohol and coffee, certainly, but also things like weight gain—I came to disagree somewhat with the official recommendations. This is where another part of my training as an economist came in: I knew enough to read the data correctly.

A few years ago, my husband wrote a paper on the impact of television on children’s test scores. The American Academy of Pediatrics says there should be no television for children under two years of age. They base this recommendation on evidence provided by public health researchers (the same kinds of people who provide evidence about behavior during pregnancy). Those researchers have shown time and again that children who watch a lot of TV before the age of two tend to perform worse in school.

This research is constantly being written up in places like the New York Times Science section under headlines like SPONGEBOB THREAT TO CHILDREN, RESEARCHERS ARGUE. But Jesse was skeptical, and you should be, too. It is not so easy to isolate a simple cause-and-effect relationship in a case like this.

Imagine that I told you there are two families. In one family the one-year-old watches four hours of television per day, and in the other the one-year-old watches none. Now I want you to tell me whether you think these families are similar. You probably don’t think so, and you’d be right.

On average, the kinds of parents who forbid television tend to have more education, be older, read more books, and on and on. So is it really the television that matters? Or is it all these other differences?

This is the difference between correlation and causation. Television and test s...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPenguin Books

- Publication date2014

- ISBN 10 0143125702

- ISBN 13 9780143125709

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Number of pages368

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Expecting Better: Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom Is Wrong--and What You Really Need to Know

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # DADAX0143125702

Expecting Better: Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom Is Wrong--and What You Really Need to Know by Oster, Emily [Paperback ]

Book Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 9780143125709

Expecting Better: Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom Is Wrong--And What You Really Need to Know (Paperback or Softback)

Book Description Paperback or Softback. Condition: New. Expecting Better: Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom Is Wrong--And What You Really Need to Know 0.68. Book. Seller Inventory # BBS-9780143125709

Expecting Better: Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom Is Wrong--and What You Really Need to Know

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New! Not Overstocks or Low Quality Book Club Editions! Direct From the Publisher! We're not a giant, faceless warehouse organization! We're a small town bookstore that loves books and loves it's customers! Buy from Lakeside Books!. Seller Inventory # OTF-S-9780143125709

Expecting Better: Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom Is Wrong--and What You Really Need to Know (The ParentData Series)

Book Description Soft cover. Condition: New. 1st Edition. Seller Inventory # ABE-1653788441920

Expecting Better : Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom Is Wrong--and What You Really Need to Know

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 20274107-n

Expecting Better Format: Paperback

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New. Seller Inventory # 9780143125709

Expecting Better: Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom Is Wrong--and What You Really Need to Know

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # BKZN9780143125709

Expecting Better: Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom Is Wrong--and What You Really Need to Know (The ParentData Series)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # 0143125702

Expecting Better: Why the Conventional Pregnancy Wisdom Is Wrong--and What You Really Need to Know (The ParentData Series)

Book Description Condition: New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition. Seller Inventory # bk0143125702xvz189zvxnew